25th Sunday of Ordinary Time

Reflection: Dealing with oppressors

By SISTER MARY McGLONE

Amos said, “Hear this, you who trample on the needy!”

Eight hundred years later, Jesus wove a puzzle/parable using economics to illustrate the message. Paul explains that when the power of those trampling on the needy makes justice seem impossible, we must turn to prayer.

Today’s Gospel tells a story that seems to be about a steward whose master was impressed by his clever manipulations. Is Jesus’ point that when about to lose a job, you should intensify your malpractice to cushion a nest for the day when you’re out of work? That’s what it seems like. Jesus says, “The children of this world are more prudent … than the children of the light.”

What? The “worldly” are more prudent?

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1806), “Prudence is the virtue that disposes practical reason to discern our true good … and to choose the right means of achieving it.” So, the steward who worked fast behind his employer’s back was discerning good and acting for it? How?

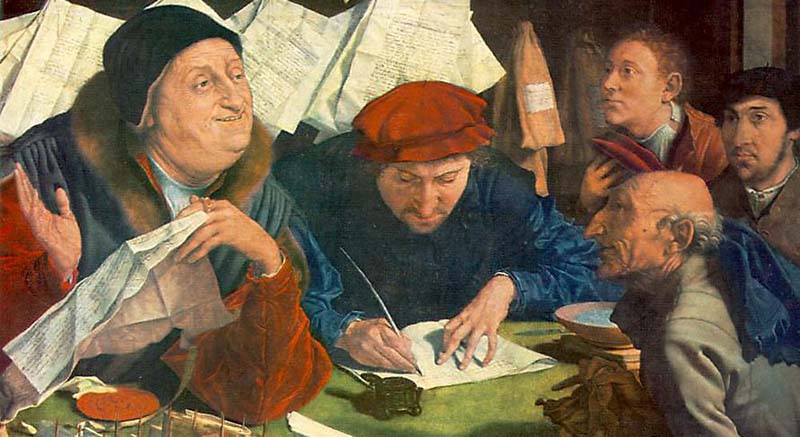

Biblical scholar N.T. Wright offers an interesting perspective on this story. He points out that Scripture prohibited the lending of money for interest. Therefore, what some clever folks did was lend in kind: olive oil, wheat, etc. on which they could collect interest. Wright suggests that the book-cooking steward went to the debtors and bargained for exactly what they had borrowed, erasing the exorbitant interest the master was charging.

In the end, the steward had made a lot of friends on whom he could count when the time came. The duped master had little recourse. He had found a way around the law; bringing the servant to “justice” would have exposed him as a scoundrel. Besides, he wasn’t really losing anything — he got back what he had lent out — which was the intent of the law. Not only that, but, like it or not, the steward’s action brought the master back to the realm of justice. He was no longer trampling the needy or writing them off like a pair of sandals. Folks who understood Jesus’ point went home laughing.

On the way home, they may have mulled over the message: “That’s a shrewd way to deal with our own, with people who say they believe what we do and who will feel shame when caught. What about the ones who have all the power and oppress us?”

Paul gives Timothy some very practical advice about dealing with oppressors. First, he says, pray for “all in authority that we may live a quiet and tranquil life.” In other words, “pray for your enemies and don’t poke the bear.” But there’s more. He adds that God wants everyone to be saved through Christ who excluded no one. Paul ends by counseling all to pray without anger or argument — an attitude that requires hard and generous prayer when it comes to people who make life harder for others.

The combination of these two readings with Amos’ warning to those who destroy the poor, takes us into the ambiguous territory if we want to convert a parable into practice. Sometimes the kind of question a 5-year-old could answer helps us make a good judgment: “In Jesus’ parable, who did the most good for others?” Obviously, the steward, seemingly the most dishonest of them all. What does that tell us?

Jesus was a master at undermining systems. Instead of fixating on clear rules and regulations, he saw beneficiaries and underdogs created by well-controlled social structures. He saw that debtors were caught in a vicious circle of increasing interests, that poor widows had very little chance to survive in a dignified manner, that the blind and lame were blamed for disabilities over which they had no control. He was not pleased with what he saw and taught that it grieved God as well. What to do?

Jesus says, “Be shrewd as serpents and simple as doves.” Doesn’t that describe the steward? He harmed no one and his activity helped the poor, invited the master beyond a life of usury and saved his own skin at the same time. Jesus seems to say that some laws don’t merit obedience — at least not in God’s eyes.

Today we’re asked what we want to serve or obey. Is it law? Is it our own good? Is it the so-oft forgotten common good?

What are we to do?

First, pray. Pray for the intention of doing good for all. Review who we include in the “all” we consider. Ask for a generous heart. Pray for a clear vision of what is really happening. Pray for inspiration and the creative courage needed to carry out the urgings of a critical conscience. And then, let the Spirit and your critical conscience be your guide.

Reading 1

(Amos 8: 4-7)

Hear this, you who trample upon the needy

and destroy the poor of the land!

“When will the new moon be over,” you ask,

“that we may sell our grain,

and the sabbath, that we may display the wheat?

We will diminish the ephah,

add to the shekel,

and fix our scales for cheating!

We will buy the lowly for silver,

and the poor for a pair of sandals;

even the refuse of the wheat we will sell!”

The LORD has sworn by the pride of Jacob:

Never will I forget a thing they have done!

Responsorial Psalm

(Psalm 113:1-2, 4-6, 7-8 )

Reading 2

(1 Timothy 2: 1-8)

Beloved:

First of all, I ask that supplications, prayers,

petitions, and thanksgivings be offered for everyone,

for kings and for all in authority,

that we may lead a quiet and tranquil life

in all devotion and dignity.

This is good and pleasing to God our savior,

who wills everyone to be saved

and to come to knowledge of the truth.

For there is one God.

There is also one mediator between God and men,

the man Christ Jesus,

who gave himself as ransom for all.

This was the testimony at the proper time.

For this I was appointed preacher and apostle

— I am speaking the truth, I am not lying —,

teacher of the Gentiles in faith and truth.

It is my wish, then, that in every place the men should pray,

lifting up holy hands, without anger or argument.

Gospel

(Luke 16: 1-13)

Jesus said to his disciples,

“A rich man had a steward

who was reported to him for squandering his property.

He summoned him and said,

‘What is this I hear about you?

Prepare a full account of your stewardship,

because you can no longer be my steward.’

The steward said to himself, ‘What shall I do,

now that my master is taking the position of steward away from me?

I am not strong enough to dig and I am ashamed to beg.

I know what I shall do so that,

when I am removed from the stewardship,

they may welcome me into their homes.’

He called in his master’s debtors one by one.

To the first he said,

‘How much do you owe my master?’

He replied, ‘One hundred measures of olive oil.’

He said to him, ‘Here is your promissory note.

Sit down and quickly write one for fifty.’

Then to another the steward said, ‘And you, how much do you owe?’

He replied, ‘One hundred kors of wheat.’

The steward said to him, ‘Here is your promissory note;

write one for eighty.’

And the master commended that dishonest steward for acting prudently.

“For the children of this world

are more prudent in dealing with their own generation

than are the children of light.

I tell you, make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth,

so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.

The person who is trustworthy in very small matters

is also trustworthy in great ones;

and the person who is dishonest in very small matters

is also dishonest in great ones.

If, therefore, you are not trustworthy with dishonest wealth,

who will trust you with true wealth?

If you are not trustworthy with what belongs to another,

who will give you what is yours?

No servant can serve two masters.

He will either hate one and love the other,

or be devoted to one and despise the other.

You cannot serve both God and mammon.”