These excerpts were taken from a feature article for the 2017 November Issue of “Celebration” © Celebration Publications.

By the REV. CHRISTOPHER DeGIOVINE

I love the month of November. In polite conversation with family and friends I have been making this pronouncement for years. Most think I am melancholic or depressed to enjoy a month as stark as November.

But I love the month of November. I should also say that I live in Upstate New York where November brings many gray, cold and dreary days. I love them.

I like to sit beside a still lake and simply let the quiet and the silence envelop me. The leaves are off the trees and I can once again see farther on my hikes than I could in the lush summer months when the leaves blocked the vistas. The cold of November needs warm cabin fires to dispel the chill and invite quieter moments of reflection. The diminishing daylight forces me to spend less time in frenetic activity and to slow down and simply be present to the changes of the season.

The brown and dark gold of the remaining leaves on the trees, rather than the superabundant palette of varied colors that was October, encourage a more considered, deeper reflection on things ending that I am no longer afraid to consider. The early snows remind me of the stark beauty of deep winter and the promises of a different beauty in black and white and gray.

Recently, I came across a quote by Benedictine Sr. Joan Chittester in her book “Uncommon Gratitude:” “Darkness deserves gratitude. It is the alleluia point at which we learn to understand that all growth does not take place in the sunlight. November welcomes in the darkness and deserves our gratitude.”

November is also the month in which the church invites us to ponder our beloved dead, the communion of saints (and souls). The church also invites us to be reflective and to consider the deeper mysteries of our faith in this month. In his Pulitzer Prize winning book, “The Denial of Death,” Ernest Becker in 1974 argued that we in the West live in two worlds: the physical world that ends in death and the symbolic world that tries to make sense of (Becker would argue “denies”) death.

Becker invites us to face, clearly and without the biases of symbols and metaphors, our own dying. Becker believes that, in an age of reason, our religious metaphors and symbols no longer help us face our mortality. He also argues that science has tried to replace religious metaphor but is unable to do so. Becker believes that we need new symbols and metaphors (he calls them “illusions”) that can help us face our mortality. …

Ilia Delio, a Sister of St. Francis of Washington, D.C., has been trying to use modern science, especially quantum physics to explain our “poetic” understanding of these “natural” truths.

In a reflection called “God is always new,” Delio reflects on a quote by Teilhard de Chardin, “Le toujours Noveau Dieu,” translated as “God is always new.”

Delio writes: “I was immediately struck by Teilhard’s words because I have been pondering the newness of God for quite some time. Teilhard realizes that God does not simply do new things but God is always new. The Dominican mystic Meister Eckhart had a similar insight several centuries ago when he wrote: ‘God is the newest thing there is, the youngest thing there is. God is the beginning and if we are united to God we become new again.’”

It is this possibility for newness; this hunger for new metaphors and symbols; this facing of mortality itself; this pondering of the great mystery of life, death and rebirth that is November.

November invites us into that space that is beyond words, into the silence of God. November invites us to find new ways to speak of the great mystery of death and life especially of those we have loved and of all who have gone before us.

What happens when I die? Will I see my mother and father again? What will heaven be like? Are all the people I love in heaven? Will I know my loved ones in heaven? These questions are often heard by ministers who listen to those who grieve the loss of loved ones.

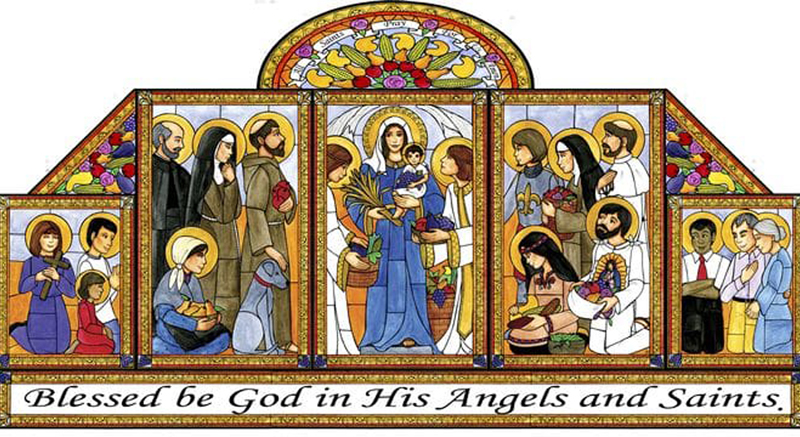

The images we have of the great mystery of life after death, of heaven (or hell), of the communion of saints is rich and varied. November is traditionally the month in which we remember all those who have gone before us, souls and saints of God. With the diminished emphasis on purgatory as a kind of anteroom awaiting our entrance into heaven, the distinction between souls and saints has become cloudy.

Our old images no longer may be as helpful as they once were for us to approach this great mystery that all our beloved, in some significant way, remain with us in the communion of saints. Science and especially quantum physics has begun to challenge and change even how we understand death and dying. So, the invitation to our God who is ever new, always calling us into new ways of being and understanding, may be more critical now than ever.

In this post-modern, quantum world are there new images that could help us understand church teaching on what happens when we die? Might some new approaches to understanding our deceased and how they do and do not remain with us help those who are still on the way?

In the Gospels when Jesus appears to Mary Magdalene and to the other disciples, he is often mistaken for someone else. It takes a call, a meal, the breaking of the bread to have our eyes opened and our hearts enlivened to recognize that we are in the presence of the Lord. When confronted with trying to explain what life after death might be like, St. Paul says: “There are both heavenly bodies and earthly bodies, but the brightness of the heavenly is one kind and that of the earthly another. The brightness of the sun is one kind … the brightness of the stars another. … So also is the resurrection of the dead. It is sown corruptible; it is raised incorruptible. It is sown dishonorable; it is raised glorious. It is sown weak; it is raised powerful. It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual one.” (1 Corinthians 15:40-44)

Paul uses the metaphors of his day, heaven and earth, sun and stars to explain the mystery of life after death. Paul, in his time, was reaching for new ways to express the concept of resurrected life. Could the metaphors of our time help us to understand and convey what we mean when we speak of the communion of saints?

As an example, might the Jungian concept of the “collective unconscious” or the soul of humanity be a metaphor for the consciousness of God? Might then our individual understanding and awareness be a participation in the consciousness of God? Is it possible that the consciousness of each individual is held collectively in the mind of God? Then when our earthly sojourn is ended we return to the collective mind of God where the communion of all the saints resides and where we all await the resurrection of the body.

November invites these reflections with open arms. November gives us the space free of clutter, the limited sunlight to see in the dark, the encouragement to remember our beloved dead and wonder and pray and know them still present to us in ways that only the “poetic” can capture. November takes us to the brink of what we can know and asks us to risk going farther. But for that next step we need faith and poetry.

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973), the Polish sculptor once said: “All my life as an artist I have asked myself: What pushes me continually to make sculpture? I have found the answer. Art is an action against death. It is a denial of death.”

Faith is not a denial of death; it is an acceptance of death as a way into new life. It is the door into the great mystery, ever new, that is God calling us. November is the invitation.

On Nov. 1, we will celebrate as a believing people the communion of the saints. In the preface for the Mass that day, we will pray: “It is truly right and just, our duty and our salvation ,always and everywhere to give you thanks, Lord, holy Father, almighty and eternal God. For today by your gift we celebrate the festival of your city, The heavenly Jerusalem, our Mother, where the great array of our brothers and sisters already gives you praise. Towards her, we eagerly hasten as pilgrims advancing by faith, rejoicing in the glory bestowed upon those exalted members of the Church, through whom you give us, in our frailty, both strength and good example …”

We are invited to continue to know those who have gone before us as still with us in communion. We are challenged in these times to think of new metaphors and symbols, in poetry, art, song and liturgy to reach for new ways to speak of those who have gone before us as still among us in communion.

God is calling us to ever new ways of understanding the great mystery of death and life which November invites. Let us be faithful to the challenge of finding ways to speak about what we believe that are faithful both to science and to poetry, to the great truths of our faith and to the richness to which faith calls us.

Perhaps this should be our new prayer of the saints, that they who now know the mystery more fully than we, might teach us both a humility and a courage to face our world as it grows and develops, searches and stretches, learns and unlearns how we are called to be followers of Christ, disciples of the Lord.

November invites us into the quiet reflection that so much of the rest of the year covers with noise and activity. Invite the gray, quiet silence into your soul. I invite you to sit next to a lake or the sea with the story of the salt doll as your companion. I first read this story in Anthony DeMello’s book “Song of the Bird.”

A salt doll journeyed for thousands of miles over land, until it finally came to the sea.

It was fascinated by this strange moving mass, quite unlike anything it had ever seen before.

“Who are you?” said the salt doll to the sea.

The sea smilingly replied, “Come in and see.”

The doll waded in.

The farther it walked into the sea the more it dissolved, until there was only very little of it left. Before that last bit dissolved, the doll exclaimed in wonder, “Now I know what I am!”

November invites us to ponder our deepest mysteries with those we have loved and lost and finally understand who we are.

The Rev. Christopher DeGiovine serves as pastor of St. Matthew’s Church in Voorheesville. In addition to being former dean of Spiritual Life and chaplain at The College of Saint Rose in Albany, he was adjunct professor at St. Bernard’s Institute of Theology.