A Time for new vision, hope and light

St. Lucy’s Feast Day (Lucia Day) comes annually in the middle of Advent on Dec. 13. St. Lucy is the patron saint of vision, a blessed gift we need more than ever now.

It is a wonderful coincidence that we are shepherded in our diocese by a visionary — Bishop Douglas Lucia (whose last name reflects St. Lucy).

Also in 2020, the Feast of St. Lucy fell on the Third Sunday of Advent (Gaudete Sunday).

St. Lucy, the patron saint of vision, is not normally connected to Advent in Christian thought, even though her feast day always falls during the Advent season and originated during the time thought of as the Winter Solstice. It is noteworthy, however, that tradition tells us that Lucy wore a lighted wreath on her head to help Christians who suffered in the darkness of the catacombs.

In our parish heritage, St. Lucy was important to our ancestors. We have a statue of St. Lucy and also a stained-glass window dedicated to her. Let us pray that we can bear the faith of our ancestors during this Advent season of hope.

St. Lucy’s Day celebrations

Lucy was an early 4th-century virgin martyr under the emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians. According to legend, she brought food and aid to Christians hiding in the Roman catacombs, wearing a candlelit wreath on her head to light her way and leave her hands free to carry as much food as possible.

Her feast day, which coincided with the shortest day of the year prior to calendar reforms, is widely celebrated as a festival of light. Falling within the Advent season, St. Lucy’s Day is viewed as a precursor of Christmastide, pointing to the arrival of the Light of Christ in the calendar on Christmas Day.

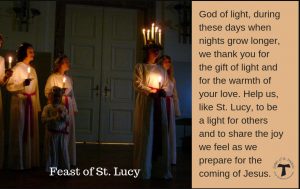

St. Lucy’s Day is celebrated most widely in Scandinavia and in Italy, with each emphasizing a different aspect of her story. In Scandinavia, where Lucy is called Santa Lucia in Norwegian and Danish and Sankta Lucia in Swedish, she is represented as a lady in a white dress symbolizing a baptismal robe and a red sash symbolizing the blood of her martyrdom, with a crown or wreath of candles on her head.

In Norway, Sweden and Swedish-speaking regions of Finland, as songs are sung, girls dressed as St. Lucy carry cookies and saffron buns in procession, which symbolizes bringing the Light of Christ into the world’s darkness. In both Protestant and Catholic churches, boys participate in the procession as well, playing different roles associated with Christmastide, such as that of St. Stephen. The celebration of St. Lucy’s Day is said to help one live the winter days with enough light.

Special devotion to St. Lucy are practiced in the Italian regions of Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige, and in Sicily, as well as in the Croatian coastal region of Dalmatia. In Hungary and Croatia, a popular tradition on St. Lucy’s Day involves planting wheat grains that grow to be several centimeters tall by Christmas Day, representing the Nativity of Jesus.

St. Lucy’s life

According to the traditional story, Lucy was born of rich and noble parents about the year 283. Her father was of Roman origin, but died when she was five years old, leaving Lucy and her mother without a protective guardian. Although no sources for her life-story exist other than in hagiographies, St. Lucy, whose name Lucia refers to “light” is known to have been a Sicilian saint who suffered a sad death in Siracusa, Sicily, about 310.

A devout Christian who had taken a vow of virginity, her mother betrothed her to a pagan. She was seeking help for her mother’s long-term illness at the shrine of St. Agatha when the saint appeared to her in a dream beside the shrine. St. Agatha told Lucy that the illness would be cured through faith, and Lucy was able to convince her mother to cancel the wedding and donate the dowry to the poor.

Enraged, her suitor then reported her to the governor for being a Christian. According to the legend, she was threatened to be taken to a brothel if she did not renounce her Christian beliefs, but they were unable to move her, even with a thousand men and fifty oxen pulling. Instead they stacked materials for a fire around her and set light to it, but she would not stop speaking, insisting that her death would lessen the fear of it for other Christians and bring grief to non-believers. One of the soldiers stuck a spear through her throat to stop these denouncements, but to no effect. Another gouged out her eyes in an attempt to force her into complacency, but her eyes were miraculously restored. St. Lucy was able to die only when she was given the Christian Last Rites.

In one story, St. Lucy was working to help Christians hiding in the catacombs during the terror under the Roman Emperor Diocletian, and in order to bring with her as many supplies as possible, she needed to have both hands free. She solved this problem by attaching candles to a wreath on her head.

Special celebrations in Italy

St. Lucy is the patron saint of the city of Siracusa (Sicily). On Dec. 13, a silver statue of St. Lucy containing her relics is paraded through the streets before returning to the Cathedral of Syracuse. Sicilians recall a legend that holds that a famine ended on her feast day when ships loaded with grain entered the harbor. Here, it is traditional to eat whole grains instead of bread on 13 December. This usually takes the form of cuccia, a dish of boiled wheat berries often mixed with ricotta and honey, or sometimes served as a savory soup with beans.

St. Lucy is also popular among children in some regions of North-Eastern Italy, namely Trentino, East Lombardy (Bergamo, Brescia, Cremona, Lodi and Mantua), parts of Veneto, (Verona), parts of Emilia-Romagna, (Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia and Bologna), and all of Friuli, where she is said to bring gifts to good children and coal to bad ones the night between 12 and 13 December. According to tradition, she arrives in the company of a donkey and her escort, Castaldo. Children are asked to leave some coffee for Lucia, a carrot for the donkey and a glass of wine for Castaldo. They must not watch Santa Lucia delivering these gifts, or she will throw ashes in their eyes, temporarily blinding them.

In Croatia and Hungary: The planting of wheat grains

In Croatia, Hungary and some their neighboring countries, a popular tradition on St. Lucy’s Day involves planting wheat grains; nowadays this serves as symbol of the new life born in Bethlehem, with a candle sometimes placed in the middle of the new plant as a symbol of the Light of Christ that St. Lucia brings. Wheat grains are planted in a round dish or plate of soil, then watered. If the planter is kept moist, the seeds germinate and the shoots are ideally several inches high by Christmas. The new green shoots, reminding us of the new life born in Bethlehem, may be tied with a ribbon and put near or under the Christmas tree.

In the Nordic countries: Lucia presentation and singing

The pre-Christian holiday of Yule, or jól, was once the most important holiday in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. Originally the observance of the winter solstice, and the rebirth of the sun, it brought about many practices that remain in the Advent and Christmas celebrations today. The Yule season was a time for feasting, drinking, gift-giving, and gatherings, but also the season of awareness and fear of the forces of the dark.

In Scandinavia (as late as until the mid 18th century) this date was the longest night of the year, coinciding with Winter Solstice, due to the Julian Calendar being employed at that time. The same can be seen in the poem “A Nocturnal upon S. Lucy’s Day, Being the Shortest Day” by the English poet John Donne.

In Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland, Lucy (called Lucia) is venerated on December 13 in a ceremony where a girl is elected to portray Lucia. Wearing a white gown with a red sash and a crown of candles on her head, she walks at the head of a procession of women, each holding a candle. The candles symbolize the fire that refused to take St. Lucy’s life when she was sentenced to be burned. The women sing a Lucia song while entering the room, to the melody of the traditional Neapolitan song Santa Lucia; the Italian lyrics describe the view from Santa Lucia in Naples, the various Scandinavian lyrics are fashioned for the occasion, describing the light with which Lucia overcomes the darkness. Each Scandinavian country has lyrics in their native tongues. After finishing this song, the procession sings Christmas carols or more songs about Lucia.

Sweden: A feast day for the young to spread goodwill

The Swedish lyrics to the Neapolitan song “Santa Lucia” have traditionally been either Natten går tunga fjät (The Night steps heavily) or Sankta Lucia, ljusklara hägring (St. Lucy, bright mirage). There is also a modern version with simpler lyrics for children: Ute är mörkt och kallt (Outside, it’s dark and cold).

At many universities, Swedish students hold big formal dinner parties on December 13, since this is the last chance to celebrate together before most students go home to their families for Christmas.

The modern tradition of having public processions in the Swedish cities started in 1927 when a newspaper in Stockholm elected an official Lucy for Stockholm that year. Today most cities in Sweden appoint a Lucy every year. Schools elect a Lucy and her maids among the students and a national Lucy is elected on national television from regional winners. The regional Lucies visit shopping malls, old people’s homes and churches, singing and handing out gingernut cookies (pepparkakor).

Boys take part in the procession, playing different roles associated with Christmas. Some may be dressed in the same kind of white robe, but with a cone-shaped hat decorated with golden stars, called stjärngossar (star boys); some may be dressed up as “tomtenissar” (Santa’s elves), carrying lanterns; and some may be dressed up as gingerbread men. They participate in the singing and also have a song or two of their own, usually Staffan Stalledräng, which tells the story about St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, caring for his five horses.

Some trace the rebirth of the Lucy celebrations in Sweden to the tradition in German Protestant families of having girls dressed as angelic Christ children, handing out Christmas presents. The Swedish variant of this white-dressed Kindchen Jesus, or Christkind, was called Kinken Jes, and started to appear in upper-class families in the 18th century on Christmas Eve with a candle-wreath in her hair, handing out candy and cakes to the children.

Another theory claims that the Lucy celebration evolved from old Swedish traditions of “star boys” and white-dressed angels singing Christmas carols at different events during Advent and Christmas. In either case, the current tradition of having a white-dressed woman with candles in her hair appearing on the morning of the Lucy Day started in the area around Vänern in the late 18th century and spread slowly to other parts of the country during the 19th century.

A special baked bun, Lussekatt (St. Lucy Bun), made with saffron and in use as early as November, is a very popular Christmas tradition.

In Finland: Lucy, a beacon of brightness in the winter solstice

The Finnish celebrations have been historically tied to Swedish culture and the Swedish-speaking Finns. They observe “Luciadagen” a week before the Winter Solstice. St Lucy is celebrated as a “beacon of brightness” in the darkest time of year. The first records of St. Lucy celebrations in Finland are from 1898, and the first large celebrations came in 1930, a couple of years after the popularization of the celebrations in Sweden. The St. Lucy of Finland has been elected since 1949 and she is crowned in the Helsinki Cathedral. Local St. Lucies are elected in almost every place where there is a Swedish populace in Finland. The Finnish-speaking population has also lately begun to embrace the celebrations.

In Denmark: Light in the time of German occupation

In Denmark, the Day of Lucy (Luciadag) was first celebrated on December 13, 1944. The tradition was directly imported from Sweden by initiative of Franz Wend, secretary of Föreningen Norden, as an attempt “to bring light in a time of darkness”. Implicitly it was meant as a passive protest against German occupation during the Second World War but it has been a tradition ever since.

Although the tradition is imported from Sweden, it differs somewhat in that the church celebration has always been strongly centered on Christianity and it is a yearly local event in most churches in conjunction with Christmas. Schools and kindergartens also use the occasion to mark the event as a special day for children on one of the final days before the Christmas holidays, but it does not have much impact anywhere else in society.

There are also a number of additional historical traditions connected with the celebration, which are not widely observed. The night before candles are lit and all electrical lights are turned off, and on the Sunday closest to December 13, Danes traditionally attend church.

The traditional Danish version of the Neapolitan song is not especially Christian in nature, the only Christian concept being “Sankta Lucia”. Excerpt: “Nu bæres lyset frem | stolt på din krone. | Rundt om i hus og hjem | sangen skal tone.” (“The light’s carried forward | proudly on your crown. | Around in house and home | The song shall sound now.”)

In Norway: A special day for children

Like the Swedish tradition, and unlike the Danish, Lucy is largely a secular event in Norway, and is observed in kindergartens and schools (often through secondary level). However, it has in recent years also been incorporated in the Advent liturgy in the Church of Norway. The boys are often incorporated in the procession, staging as magi with tall hats and star-staffs. Occasionally, anthems of St. Stephen are taken in on behalf of the boys.

For the traditional observance of the day, school children form processions through the hallways of the school building carrying candles, and hand out lussekatt buns. While rarely observed at home, parents often take time off work to watch these school processions in the morning, and if their child should be chosen to be Lucia, it is considered a great honor. Later on in the day, the procession usually visits local retirement homes, hospitals, and nursing homes.

The traditional Norwegian version of the Neapolitan song is, just like the Danish, not especially Christian in nature, the only Christian concept being “Sankta Lucia”. Excerpt: “Svart senker natten seg / i stall og stue. / Solen har gått sin vei / skyggene truer.” (“Darkly the night descends / in stable and cottage. / The sun has gone away / the shadows loom.”)

St. Lucia: Saint in the Caribbean

In St. Lucia, a small island nation in the Caribbean named after its patron saint, St. Lucy, December 13 is celebrated as National Day. The National Festival of Lights and Renewal is held the night before the holiday, in honor of St. Lucy of Syracuse the saint of light. In this celebration, decorative lights (mostly bearing a Christmas theme) are lit in the capital city of Castries; artisans present decorated lanterns for competition; and the official activities end with a fireworks display. In the past, a jour ouvert celebration has continued into the sunrise of December 13.

Special Celebrations in United States

The celebration of St. Lucia Day is popular among Scandinavian Americans, and is practiced in many different contexts, including parties, at home, in churches, and through organizations across the country. Continuing to uphold this ritual helps people keep ties with the Scandinavian countries.

In the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), which is the successor denomination to hundreds of Scandinavian and German Lutheran congregations, St. Lucy is treated as a commemoration on December 13, in which red vestments are worn. Usually, the Sunday in Advent closest to December 13 is set aside for St. Lucy, in which the traditional Scandinavian procession is observed.

The public St. Lucia celebration in Lindsborg, Kansas is a way to display the town’s Swedish heritage and serves as a rallying point for the community. It also brings visitors to the town, which benefits the town financially.

Since 1979, Hutto, Texas, has held a St. Lucia celebration for their town at the Lutheran church. Every year a Lucia is picked from the congregation. The procession then walks around the church, sings the traditional St. Lucia song, and serves the traditional saffron buns and ginger cookies.