As stated previously in our “More Good News” magazine, our small corner of the country is blessed with multiple examples of Christian virtue. The Mohawk Valley can lay claim to several saints recognized by the Catholic Church.

In winter edition of “More Good News” we presented the story of St. Issac Jogues and the North American Martyrs of Auriesville. In this issue we discuss St. Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native American to be recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church.

Kateri was born in 1659 in the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, the very place where Jogues, the French missionary, endured some of his most difficult life events nine years before. Her mother, Tagaskouita, was Algonquian and had assimilated into the Mohawk people, possibly as a captive from a skirmish. This practice had become common to replenish native populations that were decimated by the diseases brought by European traders and missionaries.

Tagaskouita became the wife of Kenneronkwa, the chief of the Mohawk. Therefore, Kateri was a high-born woman of her people.

Though of noble birth, Kateri might have been a bit clumsy as her native name, Tekakwitha, translates as, “She who bumps into things.” Regardless, the young Kateri would learn to fend for herself as at 4 years old her parents and younger brother died in a smallpox epidemic. Though she survived, her face would carry the scars of the disease and her eyesight and general health continued to be weak for the rest of her life.

Adopted by an aunt, she learned the typical chores of the women of her people, such as processing animal skins and making clothing from them, making mats and baskets of plants, as well as how to raise and tend to crops to nourish the community.

About the time of her 10th year, Kateri’s family was forced to flee its village from an attack by the French. Her uncle, who had become chief, brokered a peace with the invaders by allowing French Jesuit missionaries to live among the Mohawk people. The goal of the missionaries was to convert the native people, but that was met with resistance. In fact, one of Kateri’s cousins had converted and abandoned the tribe to go live among the French. The chief forbade, therefore, his niece from even talking to the missionaries. The ban failed in 1669 when the Mohawk were attacked by another tribe, the Mahican, who wanted to control the local fur trade.

Kateri and other Mohawk women worked alongside the Jesuits to care for the wounded, and this exposure had a profound effect on the girl. By age 13, Kateri informed her aunt that she wanted to defy custom and not marry. In 1674, she expressed her desire to learn about Christianity to a priest. Kateri began her formal training and was baptized in 1676. Taking the name Kateri was an homage to St. Catherine. Her conversion did not sit well with her people, who ostracized her and even accused her of witchcraft.

So Kateri left her ancestral home and moved to Kahnawake, a safe community for Christian natives, near Montreal. There she was once again able to meet her cousin, and her mother’s friend took her into her longhouse. Together with a new friend, Maria-Thérèse, another native girl around her age, she grew in spirituality and conviction. The two young women pushed each other in their religious fervor. With their spiritual adviser, Father Claude Chauchetière, they became examples and teachers in their community.

Kateri challenged her faith in ways that today we might find rather Medieval. She and Marie-Thérèse practiced ritual fasting, self-mortification and asceticism (extreme self-denial), intending to bring themselves closer to God. Father Claude would have to step in at times to prevent the girls from causing themselves irreparable harm.

Even so, with her already weakened state of health, Kateri was not able to withstand the punishment. On Aug. 17, 1680, Kateri passed into the Lord’s embrace while surrounded by her community. The observers swore that upon her passing her facial lacerations from the pox disappeared and her skin became radiant (to them a sign of her blessedness). Her story of sacrifice and devotion spread far and wide through a book written by Father Claude. Her burial place became a destination for pilgrims and many miracles were attributed to her intervention.

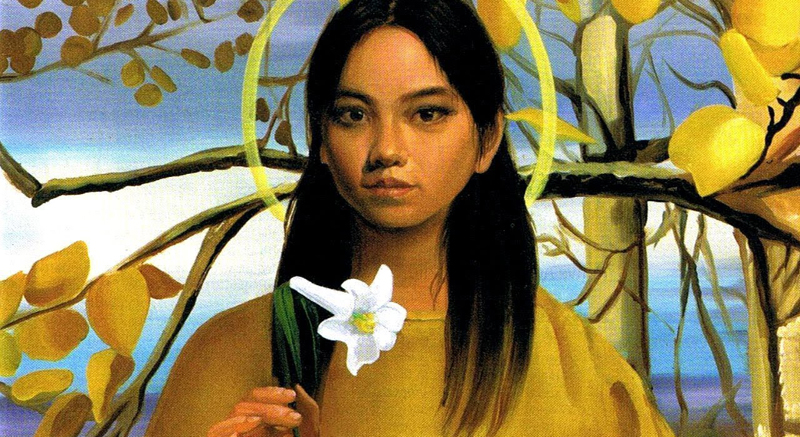

Kateri was canonized in 2012 and is known today as “The Lily of the Mohawks.”

In Fonda, just down the road from the Shrine of the North America Martyrs, there is the St. Kateri Tekakwitha Nation Shrine and Historic Site.

Although she has become a figure of veneration, the Native American community also sees her as a victim of the colonization of the Americas. She is a symbol of how life for the indigenous peoples was changed forever with the collision of their culture with that of the Europeans.

Sources: https://wams.nyhistory.org/early-encounters/french-colonies/kateri-tekakwitha/; https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-of-the-day/saint-kateri-tekakwitha/; https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=154