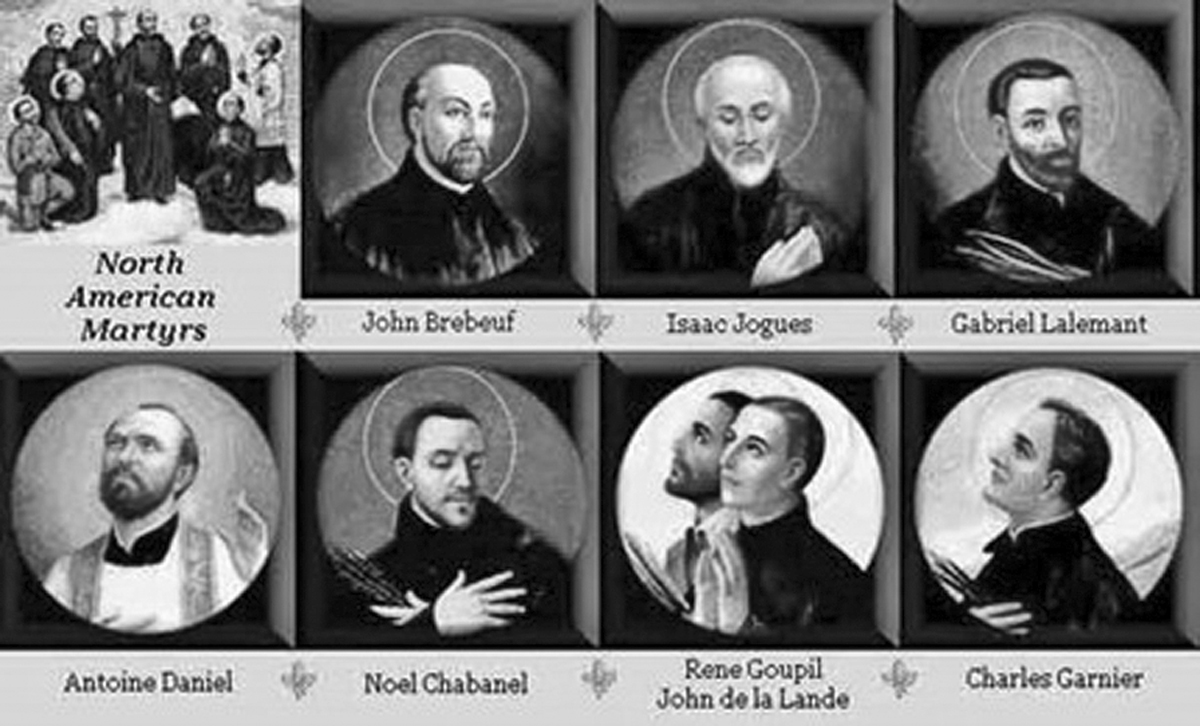

ABOVE: The Shrine of the North American Martyrs in Auriesville.

By A.J. VALENTINI

The Mohawk Valley is rich in history. From the indigenous peoples of this area and the Iroquois Confederation, through the colonial period and the American Revolution, it was a cradle of the development of our state and country even before the construction of the Erie Canal, which helped western expansion.

Our little corner of that area is rich in the growth of the Catholic faith in America. In the fall issue of this periodical, we shared the story of recently canonized St. Giovanni Battista Scalabrini, who on one of his visits to the United States (Sept. 15, 1901) blessed the cornerstone St. Mary of Mount Carmel Church.

The very first canonized saints on the North American continent have roots down the Mohawk River in Auriesville.

The very first canonized saints on the North American continent have roots down the Mohawk River in Auriesville.

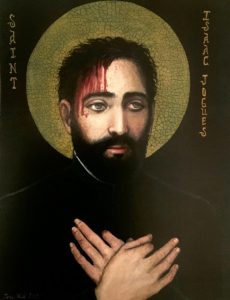

Isaac Jogues and his companions were the first martyrs of the North American continent officially recognized by the Church. St. Isaac Jogues was born at Orleans, France, on Jan. 10, 1607, and later was ordained to the priesthood.

In 1636, as a 29-year-old member of the Society of Jesus, he gave up a career as a teacher of literature in France to work among the Huron Indians in the New World. He and his companions, under the leadership of Jean de Brébeuf, arrived at Three Rivers (Trois Rivieres), a tiny French trading post on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec.

Among Father Jogues’ possessions was a small Mass kit that his mother had given him. Jogues hoped that the Hurons, who were completing their summer’s trading, would allow him to travel hundreds of miles inland with them when they returned home. He gained their confidence and respect through his physical prowess on their journeys, gathering wood, portaging their canoes and supplies, and adapting to their difficult life.

But Jogues’ positive contributions were counterbalanced by the European’s introduction of influenza among an indigenous people who had no resistance during his and his companions’ first winter among them. It was only through determination, faith and hard labor that they convinced the Hurons not to expel them.

The Hurons, who lived in the north, experienced frequent incursions from their southern neighbors, the Iroquois, who had obtained guns from the Dutch colonists. The lopsided encounters resulted in bloody outcomes, on the one side from superior arms and on the other from revenge.

In the summer of 1642, the Hurons decided that their annual trading trip to Three Rivers would be too dangerous since Iroquois war parties were infiltrating the area. Realizing that a lack of medicine and supplies would cause much suffering, Father Jogues, some Christian Hurons, and French laymen made the trip on their behalf. On their return, the group was attacked and captured by Mohawks, members of the Iroquois nation. They were driven through many villages and tortured until they arrived at Ossernenon (near present day Auriesville) with open wounds and broken bones.

Jogues faced his captivity with courage, encouraging his fellow captives to forgive their captors and offer their sufferings to God on their behalf. One captive was forced to cut off Father Jogues’ thumb to assure their captors that the missionary would never use weapons against them. Most of the captives suffered terrible deaths.

It seemed that the Mohawks were saving Jogues; however, perhaps as protection against reprisal from the French. He ended up in the service of a respected old Mohawk woman who protected him and even called him “nephew.” While acting as his “aunt’s” porter to a Dutch town, the men of the town offered to help the priest escape. A Dutch sea captain returned the broken, battered and maimed Jesuit to France. Several of his fingers had been cut, chewed or burned off. Pope Urban VIII gave him permission to offer Mass with his mutilated hands: “It would be shameful that a martyr of Christ not be allowed to drink the Blood of Christ.”

Welcomed home as a hero, Father Jogues might have sat back, thanked God for his safe return and died peacefully in his homeland, but his zeal led him back once more to the fulfillment of his dreams. In a few months he sailed for his missions among the Hurons.

In 1646, he and Jean de Lalande, who had offered his services to the missionaries, set out for Iroquois country in the belief that a recently signed peace treaty would be observed. They were captured by a Mohawk war party, and on Oct. 18, Father Jogues was tomahawked and beheaded. Jean de Lalande was killed the next day at Ossernenon.

The first of the Jesuit missionaries to be martyred was René Goupil, who with Lalande, had offered his services as an oblate. He was tortured along with Isaac Jogues in 1642 and was tomahawked for having made the Sign of the Cross on the brow of some children.

The Rev. Anthony Daniel, working among Hurons who were gradually becoming Christian, was killed by Iroquois on July 4, 1648. His body was thrown into his chapel, which was set on fire.

Jean de Brébeuf was a French Jesuit who came to Canada at the age of 32 and labored there for 24 years. He went back to France when the English captured Quebec in 1629 and expelled the Jesuits but returned to his missions four years later. Although medicine men blamed the Jesuits for a smallpox epidemic among the Hurons, Jean remained with them.

He composed catechisms and a dictionary in Huron and saw 7,000 converted before his death in 1649. Having been captured by the Iroquois at Sainte Marie, near Georgian Bay, Canada, Brébeuf died after four hours of extreme torture.

Gabriel Lalemant had taken a fourth vow — to sacrifice his life for the Native Americans. He was horribly tortured to death along with Brébeuf.

The Rev. Charles Garnier was shot to death in 1649 as he baptized children and catechumens during an Iroquois attack.

The Rev. Noel Chabanel also was killed in 1649, before he could answer his recall to France. He had found it exceedingly hard to adapt to mission life. He could not learn the language, and the food and life of the Indians revolted him, plus he suffered spiritual dryness during his whole stay in Canada. Yet he made a vow to remain in his mission until death.

These eight Jesuit martyrs of North America were canonized in 1930. A shrine on a hill overlooking the Mohawk River has been built near the spot of the martyrdom of these sainted men.

Sources: www.franciscanmedia.org; https://stisaac.org/the-life-of-st-isaac-jogues