By A.J. VALENTINI

Parishioners and guests always are impressed by the art-filled walls and ceilings when they enter St. Mary of Mount Carmel Church.

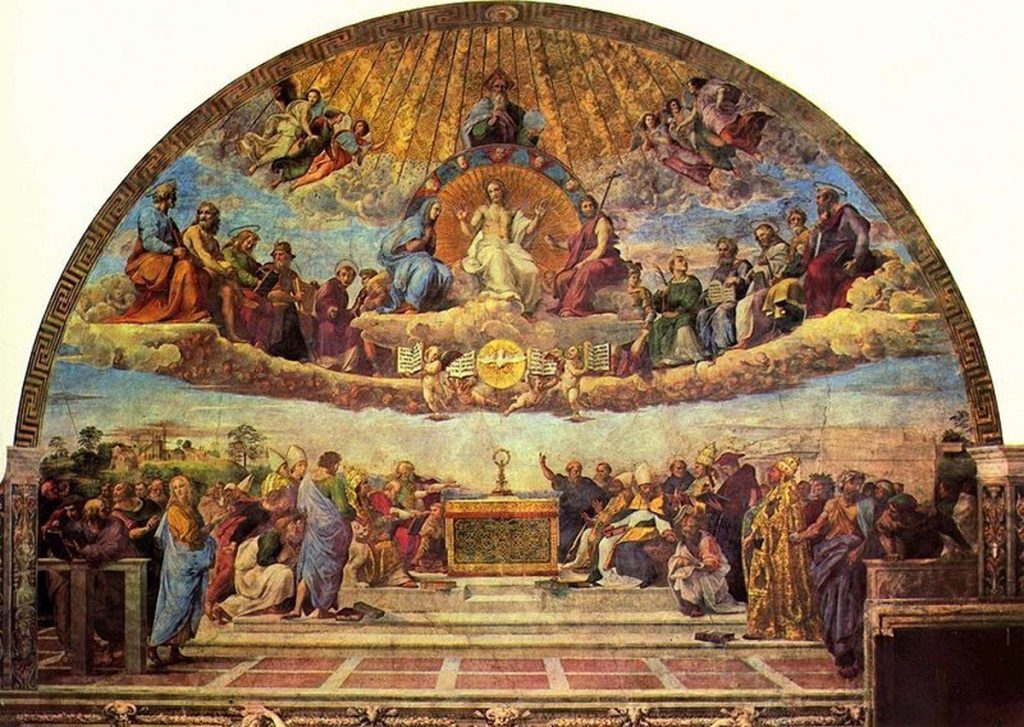

Perhaps the most admired work in the church at Mount Carmel / Blessed Sacrament Parish lies in the apse over the main altar. This impressive painting is a reproduction of the upper portion of one of the masterpieces of the great Renaissance painter Raffaello Sanzio, better known as Raphael. And like most great works of art, it has an interesting back story.

Raphael was born in 1483 in the Italian town of Urbino, one of the great centers of culture of Renaissance Italy. Its court at the Ducal palace was a magnate for artists, philosophers and other great persons of that time.

Raphael’s father, Giovanni de’Santi, was an artist by trade who worked at the palace and churches in the area, and he trained his son until he recognized that the boy’s talent far surpassed his own.

Giovanni and his son traveled to Umbria and met with Pietro Vanucci, known as il “Perugino.” Perugino’s ethereal works were so renowned that he was called to Rome and contributed some of the panel frescos that now lie below Michelangelo’s world-famous ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Perugino was impressed by the talents of his new apprentice. It was not long before Raphael was able to copy his master’s style so thoroughly that Giorgio Vasari, a contemporary and father of art history, said one could barely discern the difference between the contributions of the two. In a short time, the boy was completing commissions of his own.

In 1504, Raphael traveled to Florence to observe and study the works of other great masters. He was able to see the proposed works of Leonardo DaVinci and Michelangelo for the decoration of Palazzo Vecchio, the city’s town hall. The young artist soaked up the inspiration, and this began to alter his own style, making his work unique among all artists of his time.

In 1508, the young master received an invitation to the Papal Court upon the recommendation of the great architect Bramante, who also was from the area of Urbino and had become the principal architect of the new St. Peter’s Basilica. It is his plan that Michelangelo would later modify and bring closer to completion.

Pope Julius II commissioned Raphael to decorate a suite of rooms in the papal palace. The first, the Stanza della Segnatura was for the tribunal of the “Segnatura Gratiae et lustitiae,” the highest court of the Holy See. There, decisions were made regarding the church and the pope’s secular realm. The themes of frescoes in this room were theology, philosophy, poetry and jurisprudence.

On one wall of this room Raffaello painted the “School of Athens.” It illustrates the great philosophers of various disciplines and sciences in a mammoth classical basilica (representing the limits of man’s reason) searching for truth through reason.”

In that same room is the inspiration for the mural over the sanctuary at Mount Carmel / Blessed Sacrament.

As a counterpoint to “The School of Athens,” “The Disputation of the Holy Sacrament,” probably the first fresco the 27-year-old Raphael painted at the Vatican, focuses on faith over human reason.

The original work in Rome has two levels. The work in our church concentrates on the upper portion. Taken in its whole, the composition suggests a cruciform layout, with the vertical line delineated from God the Father down to the monstrance on the altar below. The arms of the cross are suggested by the line of honored saints flanking the Savior.

Heaven above

Two realms are depicted in the fresco: Heaven above and Earth below. Above all is the stylized version of a “velarium,” a sort of canopy that was used to shelter from the harsh sun and elements. This symbol had been used since early Christian art as a sign of heavenly protection of the faithful. The velarium here is filled with shadowy figures of angels and the blessed. In this space we see God the Father with the globe in his left hand and blessing us with his right. To the left and right of the Father, floating in the clouds are six angels.

Below the Father, Christ sits enthroned and flanked by the Virgin Mary on the left and John the Baptist on the right. Jesus came from the womb of Mary, thus sustaining the humanity of the Savior. John points to Jesus, as he was the harbinger of Christ. And just below Jesus is the dove representing the Holy Spirit.

Some artistic license was taken in the version in our church as the dove is above God the Father.

Seated in a semicircle around the throne of Christ are some of the most important personages of the Bible. This configuration recalls a classical symposium in which wise men would exchange ideas. On the left are St. Peter (with the key to the church), Adam, St. John the Evangelist (writing his Gospel), King David (with his harp), St. Steven and Jeremiah.

On the right are Judas Maccabeus, St. Lawrence, Moses (with the rays of divine light), St. Matthew (or James), Abraham (with the knife with which he was to sacrifice Isaac) and St. Paul (with a sword). In the Mount Carmel version a halo has been placed on the second character from the right. That means this person is a saint and not Isaac from the Old Testament. We surmise in this version we see St. Bartholomew, who was martyred by being flayed with a knife.

To the left and right of the dove of the Holy Spirit fly cherubs who hold the books of the gospels. The cherub on the right holds the Gospel of John and he glances upward and to our left toward that saint as he writes in his book. In our church, the pairs of angels have switched sides, but the cherub with the Gospel of John still glances toward its author.

The upper part of this fresco depicts the church triumphant in heaven, and through the wounds visible on Christ a reminder of the day of universal judgment. The lower portion of the fresco (not reproduced in our church) shows the church as militant upon Earth — thinkers, scholars and theologians do not just gather for the celebration of the Eucharist, they are engaged in an animated discussion on the mystery of it. The link between the two: a search for truth – reason versus faith.

Earth below

The characters in the lower portion of the fresco are seeking to comprehend the transubstantiation of the body and blood of Christ. The scene is populated with representatives of the church, including four doctors of the church; Sts. Dominic, Francis, Thomas Aquinas, Bonaventure, Scotus and Nicholas; Pope Julius II (the patron of Raphael and thus an homage to him); Pope Sixtus IV (dressed in gold); Savonarola (the firebrand monk responsible for the “Bonfire of the Vanities”); Dante Alighieri (the Italian poet whose mystical travel through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise in the “Divine Comedy” is the most translated and read book after the Bible); and Bramante (again, the artist shows his appreciation for the intelligence of his friend as he leans on a railing, gesturing to his book, looking at the young man to the right).

A disputation does not mean there is disagreement among the earthly characters of the lower level — it is a formal argument rather than stress disagreement. The animated figures gesture with their hands, make movements with their bodies, bend their ears, knit their brows and exhibit different facial expressions. And Raphael knits the whole composition together by repeating gestures from the Heavenly realm to that of Earth.

The uplifted finger of John the Baptist is reflected in the uplifted figure to the right of the altar below. The hands to chest of the Madonna are reflected in the figure to the left of the altar. St. Steven above points to the standing figure with the blue toga below who seems to be making a point. The conversation between Peter and Adam above is reflected across to the bottom right between the characters at the railing.

The obvious difference in the characters above from those below is that those in Heaven are serene — they “get it,” they know the truth. The mortals below are wrestling with the truth. They have yet to completely grasp it.