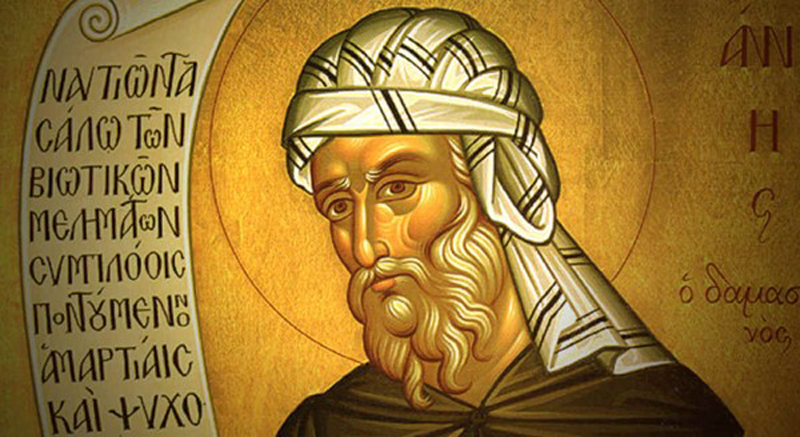

(c. 674-749)

John was a native of Syria. When it was overrun in the 630s by a new, martial religion that originated in Saudi Arabia, his family served in the local caliph’s administration.

The Muslim conquest was facilitated by the local population of subjugated, but educated, Christians and Jews who were conquered but not displaced. They carried out the everyday tasks of empire building of which the illiterate horsemen of the desert knew nothing.

John and his family were part of this large administrative class of Arabic non-Muslims. Our saint, then, personally lived the epochal transition of Syria from a Constantinople-focused Christian culture to a Mecca-facing Muslim one.

After receiving a complete education from a captive Catholic priest, John abandoned his secular career while a young adult and entered a monastery near Jerusalem to become a priest and monk. The rest of his life was dedicated to his own personal perfection and to theological and literary pursuits. Islam’s prohibition of images forced Christian theologians to defend and explain something that had never before been challenged — the ubiquitous Christian use, in public and private, of icons, statues, medals, crucifixes, and other forms of art.

John was the first to distinguish between the worship rendered to God alone and the veneration given to images and those they represent. John noted that the saint is not the paint on the wood any more than Jesus is the ink on the page of the Gospel. Such distinctions were needed to respond to both Islam and to the Old Testament strictures against the use of images, an exception to which was found, in any case, in the God-sanctioned adornments on the Ark of the Covenant.

John Damascene argued that when God took flesh, He ended the era of the misty, faceless God. Because God chose to be visible, the Christian can venerate the Creator of matter who became matter for man’s sake. Salvation was achieved via created matter, so we venerate that matter not absolutely, but contingently. Did not Christ hang on the wood of the cross? Did He not consecrate bread and wine? Was He not baptized in water?

The matter of which images are made comes from God Himself and thus shares in His goodness. Even the Sacraments make use of the elements of creation to become vehicles of God’s grace. John’s ideas won the day, long after his death, at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which condemned iconoclasm. From that point until the rise of Protestantism, art was correctly understood in Western culture as an extended celebration of the Incarnation. When we gaze in wonder at the mellow glow of stained glass, marvel at the smooth serenity of the face of Mary in Michelangelo’s Pietà, or wonder at the explosion of the baroque in an Italian church, we should whisper thanks to today’s saint for saving the day just when it needed to be saved.

St. John Damascene was declared a Doctor of the Church centuries later, in 1890. Ironically, John’s brave defense of icons was possible because he lived behind the Muslim curtain, in Syria. He lived beyond the reach of the long arm of Constantinople, a city whose emperors opposed icons partly to appease their new and violent geopolitical neighbors, the Muslims, whose mosques were adorned with geometric patterns, not faces and bodies.

Adapted by A.J. Valentini from My Catholic Life! (2020b, June 12). St. John Damascene, Priest and Doctor –. https://mycatholic.life/saints/saints-of-the-liturgical-year/december-4-saint-john-damascene-priest-and-doctor-optional-memorial/