Last Updated on May 4, 2018 by Editor

We have seen the palms of the Sunday before Easter, the washing of the feet, the cross of Christ’s martyrdom, the butter in the form of the “sacrificial lamb of God” and even Easter eggs on our tables.

In our time, American society is predominantly literate and we are able to grasp meaning from written words. In the past, written language was beyond the realm of comprehension of many. For that reason, the church through the centuries has used certain universally recognized images to tell the stories of the Bible and faith.

Iconography — from the Greek words for “image” and “to write” — is a technique of communication developed since ancient times. Icons were used in early Christianity relatively soon after the death of Christ. If you visit the catacombs of Rome, where Christians worshiped clandestinely and buried their dead, you will see images of Christ as “The Good Shepherd” and sarcophagus faces decorated with a wavy etched design borrowed from pagan tombs but, which for the Christians, represented the waters of Baptism.

In the Byzantine period there was a divide between the Eastern and Western attitude regarding images. The Eastern iconoclasts (breakers of icons) created two pushes to destroy images entirely (724-787 AD and 814-842 AD) because of the commandment forbidding the making and worship of graven images. Some people equate this movement to the growing influence of Islam in the East.

Though the use of holy images never was eliminated, the Eastern church tended to stick to a strict canon of depiction in reverence to honored traditions rather than evolve in the following centuries the way the practice did in the West.

This formulaic system of representation, because it didn’t change, was easily recognizable to the faithful. Many churches from the Byzantine era depict Jesus as “Christ Pantokrator,” that is the Lord most powerful. He is shown fixing his gaze on the viewer, often holding a page from scripture and bestowing a blessing. The background generally is in gold, because it is “pure and incorruptible,” represents God, Jesus and heaven at the same time.

Mary is depicted as the “Virgin Hodegetria,” she who shows the way. She is shown holding the child Jesus with her head inclined toward him (motherly love), and gestures to him as if to say, “He is your path to salvation.” The child in her arms gestures in blessing to the viewer as a confirmation of this message.

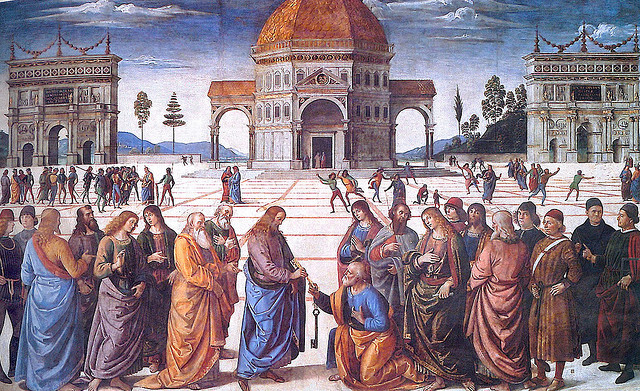

As traditions evolved, the icons of saints were incorporated pictorially and in sculpture into sacred art. Symbols developed to identify each character to the illiterate viewer and to remind those who were literate of a particular saint’s contribution. St. Peter, for example, always is portrayed with a key as he, as the first pope, was the one who received the keys to the church and salvation from Christ.

Each of the four evangelists of the New Testament has his own symbol. Often the icons, rather than their physical selves appear in the work of art. St. Mark is depicted with a winged lion that holds the Bible in one paw, symbolizing the gospel Mark wrote. The lion was believed to sleep with its eyes open, a comparison to Jesus, who though he lay in a tomb, never slept (died). The animal also is a symbol of royalty (Christ the King). The wings indicate a king not of this earth.

Matthew is symbolized by a winged angel. He is the one who traced Joseph’s ancestors all the way back to Abraham, through David. This lineage points to the human connection of Jesus and the angel is the divine.

Luke is symbolized as the winged ox, a reference to ritual sacrifice, service and strength. This symbol not only captures Jesus’ sacrifice but the call to the faithful to personal sacrifice in following Christ.

John is represented by an eagle. The ancients believed eagles could look directly into the sun, which from antiquity was equated with the Almighty. The eagle is a creature of the sky and therefore the heavens. John’s words flew across Christendom.

With all our book knowledge these days, it still can be said that a picture (or statue) remains worth a thousand words.